In the early days of November 1952, a man walked into the showrooms of Seligmann & Cie., located at 23, Place Vendôme, in Paris. His name was Mr. Veil-Picard, heir to a very substantial collection of decorative objects and other cultural assets left behind by his father and which had been looted from their Paris apartment in spring of 1944 by elements of the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR). As luck would have it, most of the crates containing Veil-Picard property (marked “WP”) were located in Germany and Austria and returned to France to be restituted to the Veil-Picard family.

|

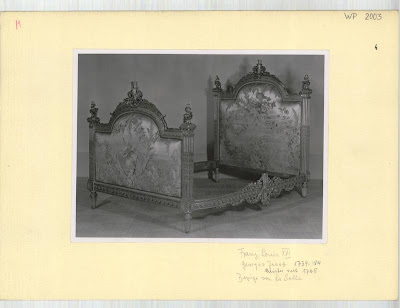

| WP 2003 Source: ERR Project via Bundesarchiv |

One of the recovered items was a bed frame, the so-called “Marie-Antoinette” bed frame. It is one of those historical oddities that is more likely to turn into a conversation piece. Legend has it that this bed frame was one of many designed to accommodate the royal body of the “Austrian Queen” wherever she might end up—castle, manor, stately apartments. No matter, as long as there was a bed specifically designed to suit her particular tastes.

According to the ERR scholars of the Jeu de Paume, the bed frame, labeled WP 2003, actually hailed from the “Palais de Versailles” and was the masterful handiwork of Georges Jacob (1739-1814). However, the description on Veil-Picard’s own inventory is humbler; it simply refers to a Louis XVI bed with designs by Philippe de la Salle. Like many stolen cultural items from across Europe, the bed ended up at Lager Peter (Alt-Aussee), the main cultural plunder depot lodged in the Austrian mountains, and returned directly to France without going through Munich.

|

| WP 2003 Source: ERR Project via NARA |

|

| WP 2003 Source: ERR Project via NARA |

Veil-Picard recovered the item on April 16, 1946.

Six years later, Veil-Picard offered the ornately-decorated bed frame for sale to François-Gérard Seligmann, general manager of Seligmann & Cie. in Paris, whose own firm, co-owned in a very complex arrangement by his brothers and cousins in Paris and New York, had been completely fleeced during the German occupation of France, some say as payback for the Seligmann family’s alleged mishandling of Hermann Goering on one of his pre-invasion shopping sprees in Paris.

Seligmann estimated the bed frame to be worth around four million francs (not more than 20,000 US dollars, 1952 value).

Although he did not really believe that the bed had been slept in by or been designed for Marie-Antoinette, Seligmann realized, however, that, as is so often the case, it made for a good story which could only enhance the value of an item that would otherwise be hard to sell, no matter how you looked at it.

All this to say that many claimants who recovered their stolen property sold it in the years that followed their restitution, some because they needed the income, others because the items no longer interested them, and for most, it was a stark reminder of a period that they just as soon would want to forget. For those who firmly believe that venality is the prime motive underlying a claimant’s desire to sell restituted property, think again. And, to be frank, once the rightful owner recovers his or her property, its ultimate fate should not be anyone’s concern except the owner’s.