by Marc Masurovsky

Most cultural institutions around the world are controlled or owned by governments. In political terms, the State oversees and controls culture, sometimes intimately, most often at a distance. There are ministries, departments, specifically tasked with the management of culture, at all levels of society.

The State allocates funds to thousands of projects, large and small, as long as it thinks that it can afford them. But it also abuses its discretion to decree what works of art remain within its territory or what works should be incorporated into its collections, forever.

To wit:

The so-called Waverley criteria are invoked to determine the validity of an export ban. Based on the Waverley criteria, the British government deems what work or object is too important to be exported. Its loss has to be construed as a “misfortune”. That sounds a bit tepid. A misfortune? How about a loss to the nation? People experience misfortunes. How does the disappearance of a work of art constitute a “misfortune”? And yet…

In 2012, a Picasso painting, “Child with a Dove,” was banned from leaving the British Isles because the government wants it to remain within its borders.

|

| Child with a Dove |

|

| Jane Austen’s ring (left) and Kelly Clarkson (right) |

|

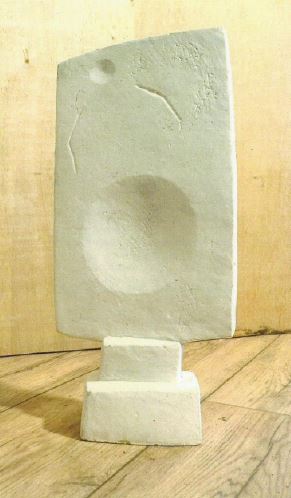

| Femme, by Alberto Giacometti |