|

| Brookdale Center, Cardozo Law School Source: Wikipedia |

This one-day symposium took place on March 31, 2011, at Cardozo Law School in downtown Manhattan.

It featured, among other things, a panel on “Nazi-Era Looted Art: Research and Restitution.” The speakers included one person from the art trade, Lucian Simmons, a vice president at Sotheby’s; Larry Kaye, of the law firm of Herrick Feinstein who co-chairs its art law group; Inge van der Vlies, who is a senior official of the Dutch Restitution Committee in Amsterdam; Lucille Roussin, co-organizer of the conference and head of the Holocaust Restitution Claims Practicum at Cardozo Law School…. and myself, as co-founder of the Holocaust Art Restitution Project and the only non-lawyer and historian in the assembly.

|

| Lucian Simmons Source: Sotheby’s |

Larry Kaye spoke about the events surrounding the seizure of the ‘Portrait of Walli’ by Egon Schiele and the involvement of his firm in the settlement of the case with the Leopold Foundation in Vienna, Austria. He also addressed some sensitive issues governing the plunder of the Goudstikker collection in Amsterdam and the postwar role of the Dutch government in not facilitating the restitution of many items in that collection.

|

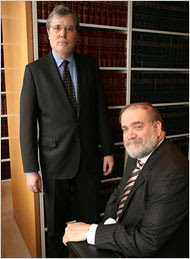

| Howard Speigler, left, and Lawrence Kaye Source: The New York Times via Fred R. Conrad |

Lucian Simmons described how Sotheby’s is leading the charge on art restitutions, careful, though, not to intrude on the rights of the consignors and the good faith purchasers, and reminding all of us that there are two victims in this game–the historical victim who lost the work or object and the good faith purchaser who–god forbid!–was caught with it, thinking it was perfectly fine. He did address an early incident involving a painting by Jakob van Ruysdael which had been withdrawn from a sale at Sotheby’s London, in October 1997 on account of its shady provenance–which indicated that it had been acquired for Hitler’s Linz Museum project.

|

| Inge van der Vlies Source: Raad Voor Cultuur |

Inge van der Vlies gave us a painstaking description of the processes involved in assessing art claims in Holland through her restitution committee, reminding us all that, had the Dutch government adhered strictly to the rule of law, no returns would have been possible to claimants because of statutory and other considerations governing ownership of works of art. Hence, its munificence in ‘doing the right thing’ governs the debate on restitution. Larry Kaye took exception to the Dutch government’s interpretation of what constitutes legally binding decisions in art restitution cases. Nothing further needs to be said here about this.

Being the historian of the group, my task was to give context to the issue of restitution. I opened up the subject writ large, going back to the Hague conventions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries which sought to define protections for civilians and their property while armies duked it out near their fields. My point, which is not popular, is that plunder of works and objects of art motivated by ideological, political, racial, and ethnic considerations are characteristic of the first half of the 20th century, starting with Armenia, going through the muddle of the First World War, Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany, the Anschluss, the establishment of a Nazi protectorate in then-Czecholovakia, the disappearance of Poland, the Nazi invasion of Western and Northern Europe, and the subsequent onslaught against the Soviet Union and southeastern Europe. Not much time left to discuss the fundaments of restitution except to indicate that market considerations reigned supreme in the immediate postwar which compelled the US government in 1946 to liberalize the art trade by quickly eliminating wartime restrictions on the imports of cultural objects into the US, without knowing what objects might be of illicit origin. The US and its allies shut down art claims in and around 1948 in their respective zones of occupation in Germany and Austria, thereby shifting the claims process to national governments in Europe and the Americas.

Howard Spiegler, Larry Kaye’s alter ego at the Art Law Group of Herrick Feinstein, delivered a genuinely entertaining lecture over lunch where he took on the critics of art restitution litigation, especially aimed at high-revenue firms such as his and Larry’s. Point well taken. Someone has to do the work. The problem since 1945? There is still no national and/or international mechanism by which claimants who cannot afford to pay legal fees can be guaranteed a satisfactory procedure through which to articulate their losses and seek redress. It’s now been 66 years since the end of the Second World War and chances are that nothing will ever happen.

The main disappointment in an otherwise productive conference was the inability of the conveners to make a link between Holocaust-era losses and cultural property disputes in the postwar era, and also to address the confusion and complications arising out of the distinction between cultural property and other types of art objects and works of art. Currently countries such as Italy are deliberately placing Holocaust- and World War II-era losses under the roof of cultural property and cultural patrimony, thus treating a painting by Claude Monet on the same basis as an antique urn. The end result? the likelihood that the object, even if restituted, cannot leave Italian territory without special permits. Something akin to what takes place in Austria with works by Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele, and in France, with any masterpiece produced on French territory.

Hopefully, at some future forum, someone will take the brave step and challenge these artificial barriers that separate antiquities from the rest of artistic production.